How do the Tesla Roadster and Nissan LEAF compare in energy use?

Tesla Roadster owners have been driving electric for a couple of years now and have built up knowledge about how much energy is required for many different routes and driving scenarios. New Nissan LEAF owners could perhaps benefit from what Roadster owners have learned, especially in the near term while charging stations are few and far between.

On August 4, 2011, we did a test to answer a couple of questions:

How does energy use in a Nissan LEAF compare to a Tesla Roadster?

Does knowing how much energy a Roadster uses for a certain drive help a LEAF owner plan the charge needed for a long drive?

The Plan

To take a first stab at figuring things out, Cathy and I joined up with her parents, Jim and Barbara Joyce, to drive a Nissan LEAF and a Tesla Roadster on an interstate freeway up a mountain pass. We wanted to compare just the two cars and eliminate as many other variables as possible. We drove up together so we had identical road and weather conditions, put the cars on cruise control to minimize driver differences, and restricted ourselves to using the fan but not air conditioning. From Roadster data collected on previous drives and also a recent LEAF drive up the same pass, we were pretty confident it could be done from the Joyces' home even cruising at 70 mph. We were right.

The Route

The Route

We started at the Joyce residence near where Washington State Highway 18 meets Interstate 90 at Exit 25. Their LEAF started with a full charge. We drove to I-90, recorded trip and energy data at the stop light at the base of the on-ramp, accelerated up to 70 mph, then locked on cruise control. We exited I-90 at Exit 52 and recorded trip and energy data at the bottom of the off-ramp. We puttered around the summit for a bit, got some lunch, then reversed the route, again recording data at the bottom of the on-ramp getting back onto I-90 and again after exiting the freeway back at exit 25.

The Results

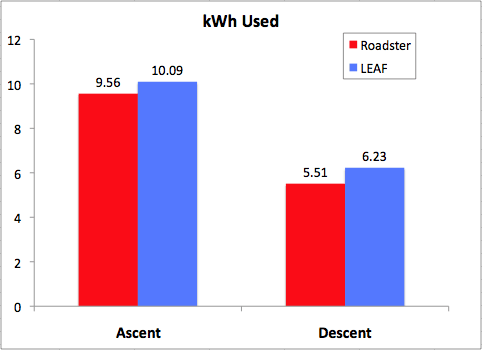

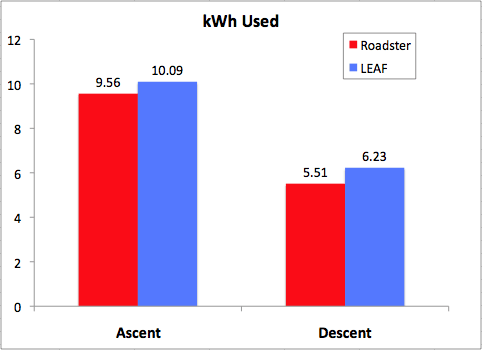

The graphs below show energy use for both vehicles up the pass from exit 25 to 52, a distance of 27 miles with a 2,000 foot elevation gain, then the descent back down from exit 52 to exit 25.

The graph shows that the LEAF used about 6% more energy than the Roadster on the way up and about 13% more energy on the way down. Both vehicles used about twice as much energy on the way up as the way down, although that ratio depends on the slope and speed. For a sufficiently steep road and slow descent, an electric vehicle can actually gain net energy driving downhill. At 70 mph, we did not see a lot of energy production, just low energy driving. At slower speeds, more energy would have been produced on the steep sections of the descent.

The graph shows that the LEAF used about 6% more energy than the Roadster on the way up and about 13% more energy on the way down. Both vehicles used about twice as much energy on the way up as the way down, although that ratio depends on the slope and speed. For a sufficiently steep road and slow descent, an electric vehicle can actually gain net energy driving downhill. At 70 mph, we did not see a lot of energy production, just low energy driving. At slower speeds, more energy would have been produced on the steep sections of the descent.

The LEAF averaged 2.7 miles per kWh (376 Wh/mi) on the way up and 4.8 mi/kWh (233 Wh/mi) on the way down, for an average of 3.3 mi/kWh (305 Wh/mi).

The Roadster averaged 2.8 miles per kWh (355 Wh/mi) on the way up and 5.5 mi/kWh (206 Wh/mi) on the way down, for an average of 3.6 mi/kWh (271 Wh/mi).

How Much Charge is Needed to Drive a LEAF Up to Snoqualmie Pass?

The LEAF doesn't give an indication of the state of charge to any useful precision, so we could only measure energy use from the trip miles and miles per kWh supplied by the LEAF. In terms of how much charge we used, the LEAF started with a full charge and ended back home with one bar showing and 4 miles on the generally worse-than-useless guess-o-meter. This included under 10 miles of driving between the freeway and home. It was a little surprising that the LEAF charge got so low given that the home-to-home energy use was only about 18 kWh, but the reported 24 kWh capacity of the battery is probably measured at a discharge rate that's lower that what's needed to climb the pass at 70 mph. Also, we know the LEAF hides some reserve charge from the driver.

From this data I conclude that starting from a full charge in Snoqualmie or North Bend, a LEAF can easily make it up and down the mountain at the speed limit without climate control. With climate control on, a bit slower speed may be required.

With a DC Quick Charge to 80% at North Bend, it could probably be done by anyone starting in the greater Seattle metro area.

Having Level 2 charging at the summit would be a big help. Even Level 1 would make a difference for someone spending the day skiing at the pass and wanting to get home with little or no charging on the way back.

Driving at lower speeds would use less charge. Really efficient driving, including better use of regenerative braking on the way down, would further decrease the charge needed.

Comparing the Nissan LEAF and Tesla Roadster

The curb weight of the Roadster is about 2,700 lbs, compared to the LEAF at 3,350 lbs. So the LEAF weighs about 25% more than the Roadster. The LEAF has a more aerodynamic shape, but has a much larger frontal cross-sectional area, so I would expect the LEAF to also have more aerodynamic drag. At freeway speeds, one would expect the aerodynamic drag to be a bigger factor in energy use, but doing a significant climb increases the importance of vehicle weight.

Because of how these two issues interact under different conditions, these numbers tell the story only for this specific drive on this route at this speed. Other drives are likely to give different results, so more tests are needed to get the full picture. It would also be interesting to do the same drive with multiple LEAFs and Roadsters to see how much variation there is between vehicles of the same model.

Data Method and Repeatability

We did everything we could both to minimize the difference between the two side-by-side drives and also standardize the drive so it could be repeated later under either similar or different conditions.

It was warm enough that we had to run the car fans to stay comfortable, but we were able to avoid use of the air conditioning.

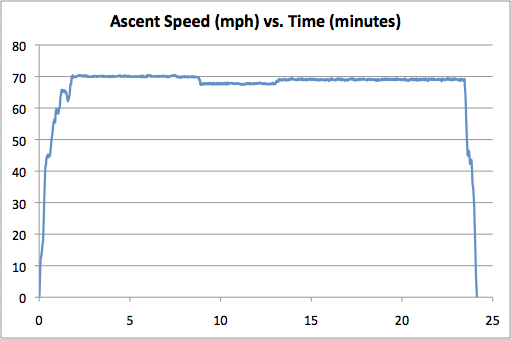

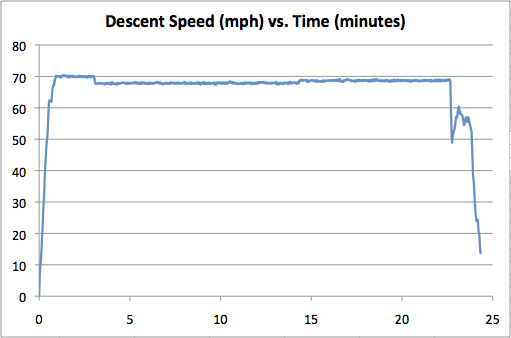

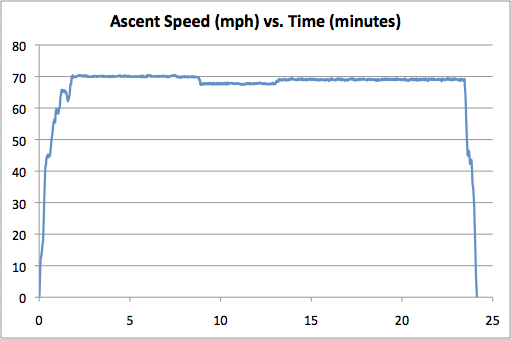

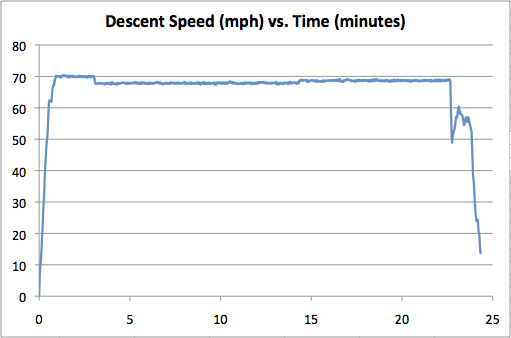

We were able to maintain 69 to 70 mph pretty well, with a couple of exceptions. Below are graphs of the Roadster's speed versus time. The LEAF speed profile would be similar, with one exception on the descent, described below.

On the way up, a few minutes after we got onto I-90, we ran into a clump of traffic we had to maneuver through, which slowed us down a little for a few minutes around the 10-minute mark.

On the way up, a few minutes after we got onto I-90, we ran into a clump of traffic we had to maneuver through, which slowed us down a little for a few minutes around the 10-minute mark.

On the way down, just a couple of miles from exiting I-90, the Roadster got boxed in between an RV at the same speed in the center lane and a slower vehicle entering just ahead of us. Rather than speed up to jump ahead of the slower vehicle (which would have used a bunch of extra energy), we slowed down sharply to let the vehicle in ahead of us. The LEAF was far enough ahead that it avoided this problem.

On the way down, just a couple of miles from exiting I-90, the Roadster got boxed in between an RV at the same speed in the center lane and a slower vehicle entering just ahead of us. Rather than speed up to jump ahead of the slower vehicle (which would have used a bunch of extra energy), we slowed down sharply to let the vehicle in ahead of us. The LEAF was far enough ahead that it avoided this problem.

Tesla Roadster owners have been driving electric for a couple of years now and have built up knowledge about how much energy is required for many different routes and driving scenarios. New Nissan LEAF owners could perhaps benefit from what Roadster owners have learned, especially in the near term while charging stations are few and far between.

On August 4, 2011, we did a test to answer a couple of questions:

How does energy use in a Nissan LEAF compare to a Tesla Roadster?

Does knowing how much energy a Roadster uses for a certain drive help a LEAF owner plan the charge needed for a long drive?

The Plan

To take a first stab at figuring things out, Cathy and I joined up with her parents, Jim and Barbara Joyce, to drive a Nissan LEAF and a Tesla Roadster on an interstate freeway up a mountain pass. We wanted to compare just the two cars and eliminate as many other variables as possible. We drove up together so we had identical road and weather conditions, put the cars on cruise control to minimize driver differences, and restricted ourselves to using the fan but not air conditioning. From Roadster data collected on previous drives and also a recent LEAF drive up the same pass, we were pretty confident it could be done from the Joyces' home even cruising at 70 mph. We were right.

The Route

The RouteWe started at the Joyce residence near where Washington State Highway 18 meets Interstate 90 at Exit 25. Their LEAF started with a full charge. We drove to I-90, recorded trip and energy data at the stop light at the base of the on-ramp, accelerated up to 70 mph, then locked on cruise control. We exited I-90 at Exit 52 and recorded trip and energy data at the bottom of the off-ramp. We puttered around the summit for a bit, got some lunch, then reversed the route, again recording data at the bottom of the on-ramp getting back onto I-90 and again after exiting the freeway back at exit 25.

The Results

The graphs below show energy use for both vehicles up the pass from exit 25 to 52, a distance of 27 miles with a 2,000 foot elevation gain, then the descent back down from exit 52 to exit 25.

The graph shows that the LEAF used about 6% more energy than the Roadster on the way up and about 13% more energy on the way down. Both vehicles used about twice as much energy on the way up as the way down, although that ratio depends on the slope and speed. For a sufficiently steep road and slow descent, an electric vehicle can actually gain net energy driving downhill. At 70 mph, we did not see a lot of energy production, just low energy driving. At slower speeds, more energy would have been produced on the steep sections of the descent.

The graph shows that the LEAF used about 6% more energy than the Roadster on the way up and about 13% more energy on the way down. Both vehicles used about twice as much energy on the way up as the way down, although that ratio depends on the slope and speed. For a sufficiently steep road and slow descent, an electric vehicle can actually gain net energy driving downhill. At 70 mph, we did not see a lot of energy production, just low energy driving. At slower speeds, more energy would have been produced on the steep sections of the descent.The LEAF averaged 2.7 miles per kWh (376 Wh/mi) on the way up and 4.8 mi/kWh (233 Wh/mi) on the way down, for an average of 3.3 mi/kWh (305 Wh/mi).

The Roadster averaged 2.8 miles per kWh (355 Wh/mi) on the way up and 5.5 mi/kWh (206 Wh/mi) on the way down, for an average of 3.6 mi/kWh (271 Wh/mi).

How Much Charge is Needed to Drive a LEAF Up to Snoqualmie Pass?

The LEAF doesn't give an indication of the state of charge to any useful precision, so we could only measure energy use from the trip miles and miles per kWh supplied by the LEAF. In terms of how much charge we used, the LEAF started with a full charge and ended back home with one bar showing and 4 miles on the generally worse-than-useless guess-o-meter. This included under 10 miles of driving between the freeway and home. It was a little surprising that the LEAF charge got so low given that the home-to-home energy use was only about 18 kWh, but the reported 24 kWh capacity of the battery is probably measured at a discharge rate that's lower that what's needed to climb the pass at 70 mph. Also, we know the LEAF hides some reserve charge from the driver.

From this data I conclude that starting from a full charge in Snoqualmie or North Bend, a LEAF can easily make it up and down the mountain at the speed limit without climate control. With climate control on, a bit slower speed may be required.

With a DC Quick Charge to 80% at North Bend, it could probably be done by anyone starting in the greater Seattle metro area.

Having Level 2 charging at the summit would be a big help. Even Level 1 would make a difference for someone spending the day skiing at the pass and wanting to get home with little or no charging on the way back.

Driving at lower speeds would use less charge. Really efficient driving, including better use of regenerative braking on the way down, would further decrease the charge needed.

Comparing the Nissan LEAF and Tesla Roadster

The curb weight of the Roadster is about 2,700 lbs, compared to the LEAF at 3,350 lbs. So the LEAF weighs about 25% more than the Roadster. The LEAF has a more aerodynamic shape, but has a much larger frontal cross-sectional area, so I would expect the LEAF to also have more aerodynamic drag. At freeway speeds, one would expect the aerodynamic drag to be a bigger factor in energy use, but doing a significant climb increases the importance of vehicle weight.

Because of how these two issues interact under different conditions, these numbers tell the story only for this specific drive on this route at this speed. Other drives are likely to give different results, so more tests are needed to get the full picture. It would also be interesting to do the same drive with multiple LEAFs and Roadsters to see how much variation there is between vehicles of the same model.

Data Method and Repeatability

We did everything we could both to minimize the difference between the two side-by-side drives and also standardize the drive so it could be repeated later under either similar or different conditions.

It was warm enough that we had to run the car fans to stay comfortable, but we were able to avoid use of the air conditioning.

We were able to maintain 69 to 70 mph pretty well, with a couple of exceptions. Below are graphs of the Roadster's speed versus time. The LEAF speed profile would be similar, with one exception on the descent, described below.

On the way up, a few minutes after we got onto I-90, we ran into a clump of traffic we had to maneuver through, which slowed us down a little for a few minutes around the 10-minute mark.

On the way up, a few minutes after we got onto I-90, we ran into a clump of traffic we had to maneuver through, which slowed us down a little for a few minutes around the 10-minute mark. On the way down, just a couple of miles from exiting I-90, the Roadster got boxed in between an RV at the same speed in the center lane and a slower vehicle entering just ahead of us. Rather than speed up to jump ahead of the slower vehicle (which would have used a bunch of extra energy), we slowed down sharply to let the vehicle in ahead of us. The LEAF was far enough ahead that it avoided this problem.

On the way down, just a couple of miles from exiting I-90, the Roadster got boxed in between an RV at the same speed in the center lane and a slower vehicle entering just ahead of us. Rather than speed up to jump ahead of the slower vehicle (which would have used a bunch of extra energy), we slowed down sharply to let the vehicle in ahead of us. The LEAF was far enough ahead that it avoided this problem.